In an era where microbiome research reveals significant insights into human health, ecosystems and disease, researchers face a central challenge: making sense of fragmented sequencing data. They must piece together millions of DNA fragments to reconstruct the genomes of thousands of microorganisms in a single sample—a task that demands sophisticated algorithms and novel methods to interpret complex data.

Marcus Fedarko, a postdoctoral associate at the University of Maryland Institute for Advanced Computer Studies (UMIACS), is tackling this problem head on. He has returned to the University of Maryland, his alma mater, to continue his work in bioinformatics.

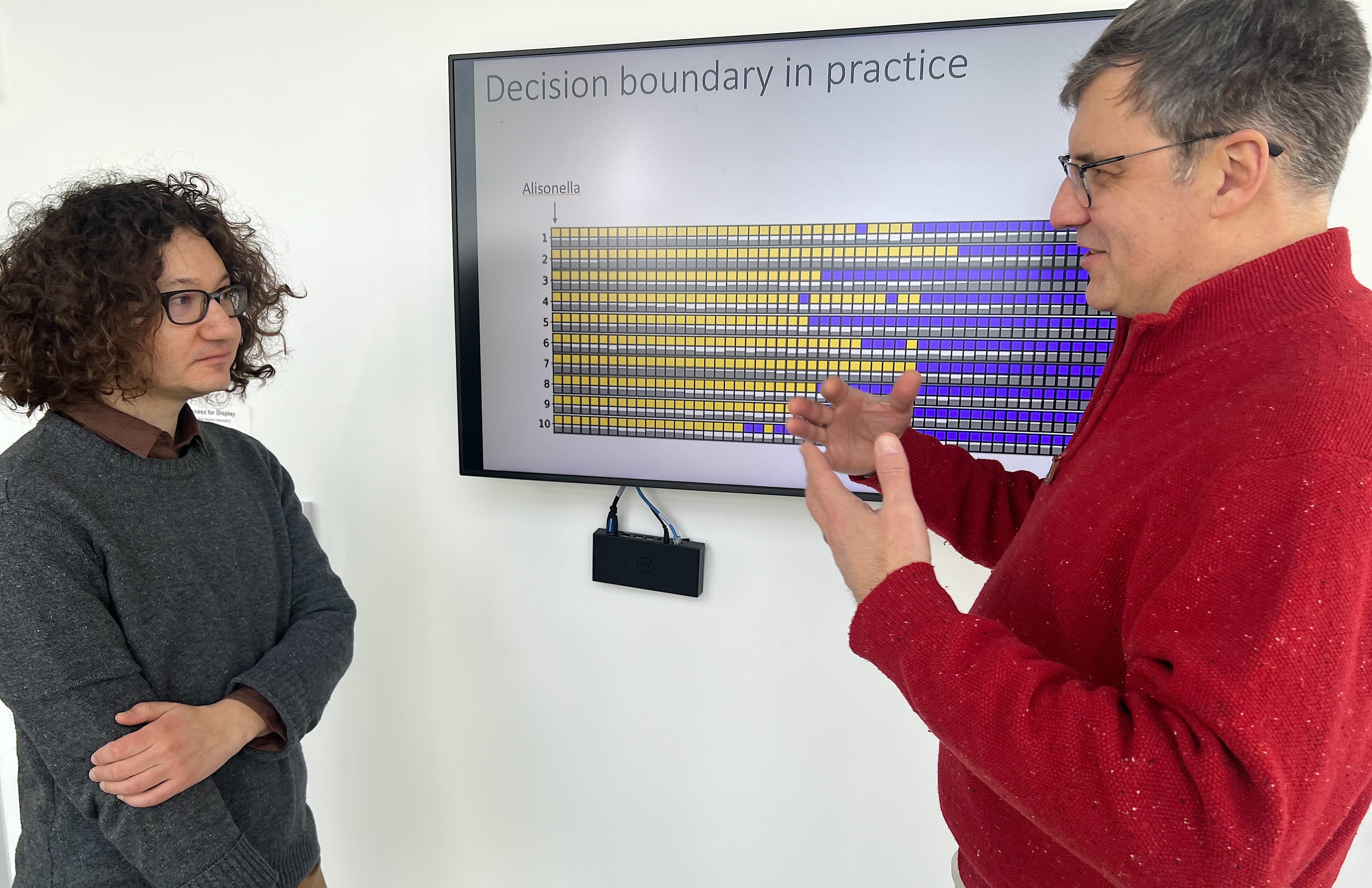

This includes reconnecting with Mihai Pop, an MPower Professor of computer science, whom Fedarko worked with as an undergraduate before earning his bachelor of science degree in computer science in 2018.

“It’s a pleasure to have Marcus rejoin my lab,” says Pop, who holds an appointment in UMIACS and is a member of the Center for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology (CBCB). “His deep understanding of graph algorithms and practical experience in analyzing biological datasets will be an asset to our efforts to understand strain-level diversity in microbial communities.”

Fedarko’s research focuses on developing software to help scientists assemble and analyze metagenomic data, making it easier to untangle networks of microbial genomes hidden within environmental and biological samples.

“Metagenome assembly is like mixing thousands of jigsaw puzzle pieces together, then trying to put the pieces in the right places without knowing what the original image looked like,” he says. “Our goal is to give researchers tools to make sense of these datasets, highlighting patterns and connections that would otherwise be nearly impossible to spot.”

Fedarko first joined Pop’s lab through CBCB’s summer internship program in 2016. That experience, he says, formed the foundation for his career. As an undergraduate, Fedarko developed a prototype tool for visualizing assembly graphs, which he presented in a 2017 poster at a graph drawing conference.

“It’s exciting to now extend that work into something more polished and usable for the wider research community,” Fedarko says. “Now that I’m back as a postdoc, I want to help foster the same open, collaborative environment for trainees that I benefited from as an undergrad.”

After UMD, Fedarko earned both a master’s and a Ph.D. in computer science from the University of California, San Diego, where he worked with leading experts in microbiome sciences and further honed his skills in visualization and genome assembly.

Fedarko’s current research is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant awarded to Pop last year. The funding supports efforts to improve metagenome assembly by combining fragmented datasets from multiple samples to create more complete genomic reconstructions.

The computational demands of this work are significant, Fedarko says. Assembly graphs can contain hundreds of thousands of nodes and edges and studying them often requires the powerful computing nodes provided by UMIACS.

“Having access to robust servers and support staff means I can focus on research, without having to worry about maintaining the hardware,” he says.

One recent focus has been restructuring the visualization software as a server-side application, which enables researchers to explore assembly graphs in flexible, dynamic ways. To help summarize massive datasets, Fedarko has also added support for treemaps—a method invented by Ben Shneiderman, Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of computer science in UMIACS—to show high-level views of large graphs.

Collaboration across disciplines is central to his work, Fedarko says.

“Working in bioinformatics requires learning the languages of both computer science and biology,” he explains. “I’ve come to appreciate how important it is to communicate clearly and adjust your explanations depending on the audience. Whether it’s biologists, programmers or students, the goal is to make complex concepts understandable without losing accuracy.”

Outside the lab, Fedarko spent four years playing clarinet in the UMD marching and pep bands as an undergraduate, an experience that helped him build community and feel at home on the sprawling College Park campus. He also maintains a running habit he started in high school, recently completing a 193-mile relay race from San Diego to Los Angeles with other graduate students and postdocs.

“Things like running help me get away from the desk and return to research with a fresh perspective,” he says.

Returning to UMD has brought Fedarko full circle.

“I really loved my time at College Park as an undergrad,” he says. “Being back allows me to apply the experience I’ve gained over the years to a problem I know well, while contributing to the campus’ vibrant research community.”

—Story by Melissa Brachfeld, UMIACS communications group