Philip Resnik, joint work with Naomi Feldman and Jackie Nelligan

Machine learning has gotten a lot of public attention recently -- programs learn to play superhuman chess by analyzing zillions of games, to label photos automatically by analyzing captions and descriptions people have given to their own pictures, or to drive cars by analyzing what human drivers do. One of the basic problems in machine learning is, if you have data to learn from that's labeled with correct answers, how do you train the machine to predict good answers for data it's never seen before?

Machine teaching turns that problem on its head. The question is, if you already know what you want the machine to learn, and you also have some model of how learning takes place, how do you pick which data to give the machine so that it learns what you want it to learn?

This is a topic that Naomi's been researching in the context of how children learn language. It's a computational modeling approach connected to a fascinating literature that suggests that, when kids acquire their first language, it's not just because they're really well equipped to analyze what people are saying --- it may also be because their parents fine-tune how they talk to kids, to make the language-acquisition process easier. Early papers, for example, talk about "motherese" having an exaggerated speech melody, simpler sentences, being highly repetitive, etc. Has nature fine-tuned the way moms (and dads!) speak to their kids so the kids can learn language more easily? How do we describe that mathematically?

Now add Jackie and me to the mix. Jackie, studying here on a Baggett Post-baccalaureate Fellowship, is a fantastic budding researcher who is interested in language and also very well equipped to tackle sophisticated mathematical problems. I'm another computational linguist who's interested in computational modeling of learning, and also particularly interested in problems related to social science.

When you put the three of us together, it turns out that you get an interesting technical question, plus an interesting social science application.

The technical question is this: what's a good way to build a mathematical model for machine teaching, if you're using vector space models to represent what's inside the head of the learner?

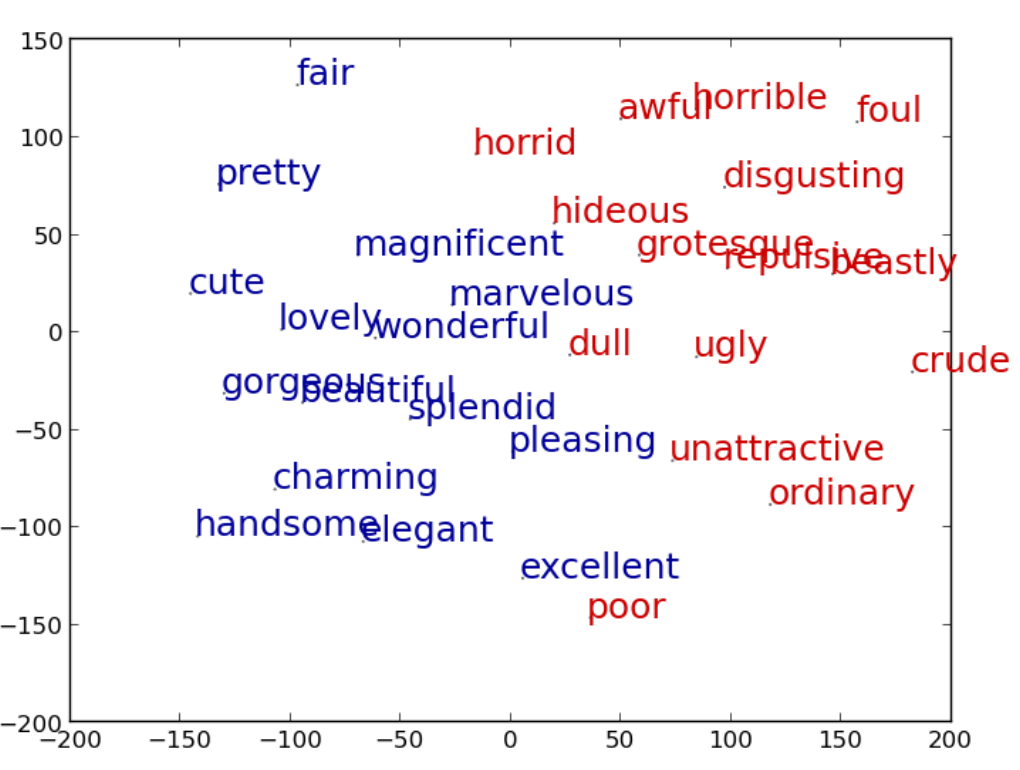

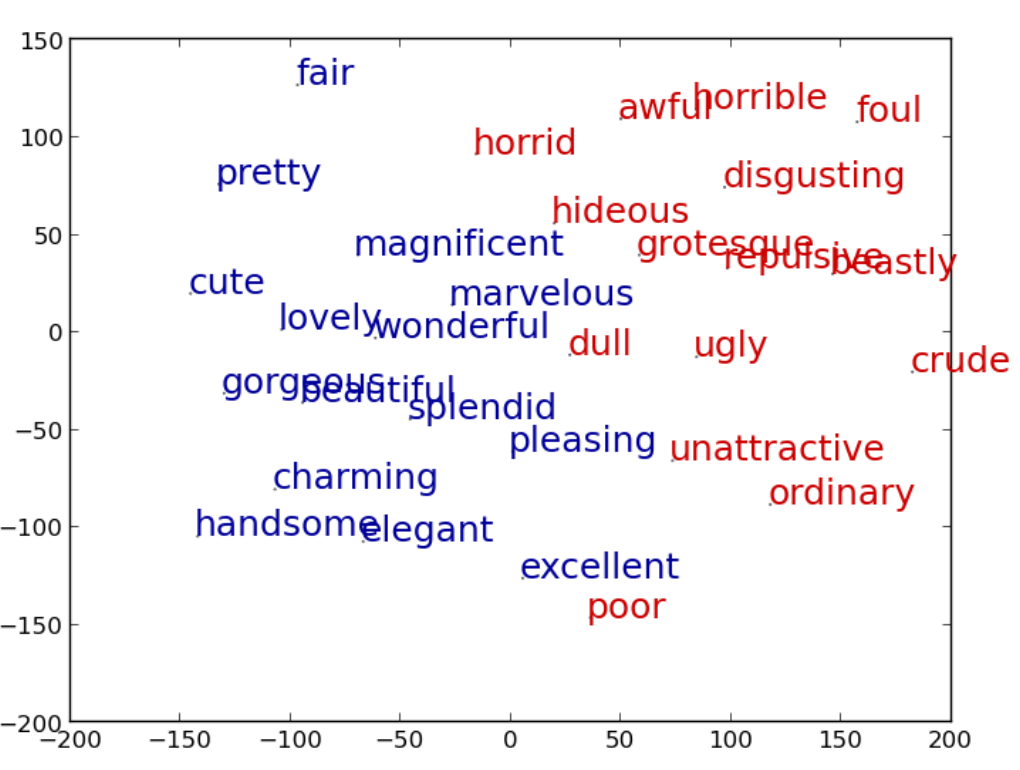

A vector space model is, basically, just a way of representing information as points in some space. For example, if you analyze a large collection of text (a "corpus") to determine which words are similar to each other, you can automatically discover that words like horrible, foul, awful, and disgusting all occupy a similar semantic "region", and words like charming, handsome, and elegant are near each other but in a different region, as visualized here in a 2-dimensional space. (The image is grabbed from this paper. The colors aren't relevant for my discussion here.)

So here's a really interesting research question. Suppose that what the learner knows is represented as a "space" like this one -- for example, the learner represented by the above picture "knows" that unattractive and ordinary are similar in meaning, because they're close to each other in the semantic space. And now suppose you wanted to give the learner new knowledge of the same kind; for example, maybe you'd like it to learn that tesguino should be considered similar to beer and wine, because it's an alcoholic beverage, and it's also similar to peyote, because both are considered sacred in cultures that consume them. What should you give the learner to read in order to come away with that knowledge? Previous mathematical models of machine teaching haven't really spent that much time looking at knowledge that's represented in this way, so Jackie has the potential to break some interesting new ground in computational modeling for machine teaching.

The second part is the social science application. People who look at political science and political communication talk about "framing", which basically means how something is talked about in relation to a particular point of view. As a very simple example, death tax and estate tax are two different ways of framing exactly the same thing. The first phrase (conservative) frames this tax as intrusive or overreaching -- "the government already taxes too much, and now you're taxing me for dying?!!" The second one (liberal) frames this tax as applying only the very wealthy -- after all, what sorts of people own estates?? Framing can have a huge influence on people's opinions, with really far-reaching consequences. For example, if the U.S. government had framed the 9/11 attacks as a crime, rather than as an act of war, events over the last fifteen years might have unfolded very differently. (See this useful discussion I just stumbled across from a course in our Dept of Communication.)

I've worked with collaborators on computational models of framing (e.g. here and here), and the work that Jackie is doing with Naomi and me has a potential application in that arena. What if we were to use vector space models (like the picture above) to describe the framing that people come way with in response to political input like speeches, debates, blogs, tweets, etc.? If you wanted people to come away with a particular framing -- for example, encouraging that immigrant and criminal should be close to each other in semantic space, or creating an outcome where marijuana is closer to medicine than to drug dealer -- what would you say to them? By modeling this computationally, using the mathematical methods Jackie's developing, we're hoping to get a clearer understanding of the ways that political speech influences public opinion. Stay tuned for word on how the research is progressing!